|

PRESUMED IMPOSSIBILITIES, continued1, 2 PHOTOGRAPHY, continued1, 2, 3, 4 PORTRAITURE, continued1, 2, 3 COMMERCIAL ART, continued1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 AUTOBIOGRAPHY, continued1, 2, 3, 4 |

|

When a Czech schoolboy, pictures of this scene made my heart palpitate, because of the lovely legends I learned associated with them. We were taught about the princess and prophetess Libuše in Czech folklore, who prophesized at the future threshold of the city: "I see a city great". ("Threshold" is "práh" in Czech, whence the Czech name "Praha" for Prague.) My affectionate feelings for Czechoslovak traditions, of which I felt part, were unfortunately marred by the anti-Semitism I encountered, existing in countries around the world. Perhaps a primary motive for it is envy of the many achievements of Jews, and the concurrent difference in their nationality, resented by original nationals. My lessons have been to put up with this attitude—which searches for the slightest grounds to justify it—as one puts up with other difficulties in life. Eventually, as made evident on this website, I came to recognition of a higher power, on whose dispensation of justice one may rely. On moving to Prague shortly after World War II, I did not have too much occasion to experience that problem, other than when a couple of times mentioning my Jewishness and consequently hearing snide remarks. Rather, I was well received in my endeavors to find work, and, as already described elsewhere here, achieved considerable success in it. 4 August 2004 It has been almost a year since the preceding, my concentration having been on other parts of this website. At present I feel I might continue with my autobiography, now some more about my life in Prague. When going there from Hungary toward the end of 1945, I had heard rumors that postwar living conditions became better in Czechoslovakia, and this turned out to be true. In Budapest, my stomach never having felt filled when living at my relatives', I often walked the streets buying with the change I had left pieces of a certain cornbread, which was about the only food sold then in the street stands, familiar in Europe. I should mention that in freedom even this form of poverty was paradise to me after the hell of the Nazis. (I avoid strong language like "hell", but I was at this moment reminded of "To Hell and Back" by Audie Murphy, that singular great hero of the war, and felt that using that word puts me in good company.) In Prague, it turned out, the street stands were back to the well known fare of what is in America known as frankfurters and knockwurst, though served differently. In Europe (at least in the countries I lived in) the meat is not served in buns, but separately, with mustard, along with a piece of bread. I was delirious, of course. As to how I managed to live, most anything was fine again compared to the recent wartime. I understandably looked for employment in which I could utilize my background in artwork. After some tries, I landed a job with a little company doing advertising art. That was where I drew the folding train shown on the COMMERCIAL ART page here. At that time I was not simply given a copy of the finished product—I was too much of an underling. It happened that sometime later I saw a copy in the window of a bookstore and went in to buy one. My living conditions were not so nice either at the start. A woman rented a larger room for sleeping to a number of males, and I became one of them. I don't think we did anything else there, I probably always ate outside. My living conditions, as a matter of fact, never were very special in Prague. There were some past acquaintances of my father who persuaded me to move into the apartment of a brother among them, who was a couple of years older than I. He was an architectural student and had a fairly nice but small apartment. After a while I in turn persuaded him that I pay half, I think, of the rent, especially after I became successful in my work. But the apartment was so tight, only one small room beside the kitchen, that I slept—and worked, when becoming a free-lancer—in the kitchen. Had I meant to stay in Prague, I would have no doubt found my own place. But I intended to emigrate to the U.S. almost from the start. I met with two cousins, older boys, on my fathers side who were in touch with siblings in America, my father also having had siblings there. The American relatives decided to get me an affidavit, a kind of license for immigration, guaranteeing their responsibility for me. As indicated above, however, my stay in Prague was no small matter in my life. It was two years or so of glory. I succeeded as a commercial artist beyond my expectations, and had I remained there, I may have gotten much further. But I don't regret emigrating. Fate after the communist takeover in 1948 was unpredictable and dangerous, and in the course of years in the States, I was able to pursue my intellectual other interests in a way I couldn't have in Czechoslovakia. Nevertheless, I include here a little more about my life in Prague. At right are two photographs of me there. I hope not to be too vain in this, but after all it is my autobiography, and pictures may add to it. The full-length one was taken on the balcony of a neighbor in the building I lived in (my friend's apartment didn't have a balcony, a feature very popular in Europe), and it was taken with my camera I used there for the black & white photographs of posters as noted, and for practically all subsequent photographs shown here on the PHOTOGRAPHY pages. I still know this because the negative is from the camera. The other photo here I didn't like much then because of my beak of a nose, but my cousin Maria, written about on preceding pages, liked it, and it is actually a good studio portrait. |

Two photos from ca.1946-7. See main text below.

|

|

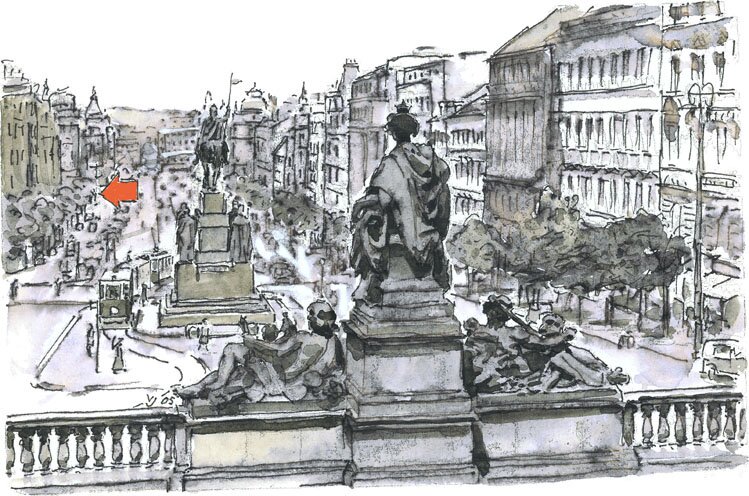

More interesting to the viewer may be my picture here of the famous Wenceslas Square (Václavské náměstί in Czech, pronounced Vahtslufskeh nahmyestyee with the "u" as in "hut" and the accented syllables underlined). Prague's main thoroughfare, it is more a broad, tree-lined and sloping, avenue than a square. In the foreground here is a frontal unit of the National Museum on top of the hill, and the sculptural unit seems influenced by Michelangelo's Medici tombs. Better known may be the statue seen preceding it of Saint Wenceslas (Svatý Václav, pronounced Svutee Vahtsluf) on horseback. The statue of the 10th-century patron saint of Bohemia was sculpted by J.V. Myslbek, who, we were taught in school, was the foremost Czech sculptor. A reason for my drawing, to be sure, is its connection with my life there. The red arrow on the left points to approximately the location, where the sloping avenue levels off, of the Melantrich publishing house (named after a known printer), where I received my commissions for the illustrations and related work in the youth magazine discussed before. This may suffice for the moment in recounting my experiences of relatively short duration in Prague. 5 July 2005 The trip to America began from that city in March 1948 on a bus, pictured near the top of the first PHOTOGRAPHY page here. As mentioned there, we went through Germany, more particularly through Nuremberg and other places on the way to Hamburg. I believe it was the first of these two cities where I took the below pictures from the bus, of the damage done by bombardment during WWII. |

|

This rubble still existed although about three years had passed since the end of the war. This is the benefit to the German people that Hitler bestowed on them. No wonder he killed himself not to face them and the world, unlike known of other rulers. |

Just another scene. |

|

|

||

|

The house in the middle background was a hollow shell, with only the walls standing, and the rest doesn't seem better. |

Sorry for showing off with all these girls, at the same stop seen in the above mentioned picture. When handing someone my camera, I usually "take charge". By pictures shown before, far left is the Czech girl, then Irene, me, the beautiful blonde, unnamed, and Olga. |

|

|

Olga, here on my left, is of course the girl I chased after, and Irene, on the other side, her sister. This is still at sea, but apparently close to disembarkment, because of the clothing and wind similar in the next picture. |

This appears to be the end of the trip, with the two sisters too, like me, prepared to meet unknown relations. I must have been unable to get a haircut along the way. I also am usually considered quiet, but somehow seem bold during this period. |

|

|

What did happen was that right at the departure by bus from Prague our congenial Czech guide emboldened us passengers to become friendly with each other, because we were to spend a lot of time together. This really seems to have affected everybody's attitude, and that's why we became like a big family. Our guide therefore deserves to be remembered by at least the small picture at right, which I fortunately took of him on board of our ship Gripsholm, where he came with us before saying goodbye Speaking a moment ago about meeting unknown relations in America, I am also fortunately in possession (I don't remember how I got hold of it) of a special old photograph showing some of them and more. I mentioned above that I met after the war with two cousins in Europe who had siblings in the U.S. Those two brothers are also in the picture, on the ground in front. But there is more, and I'll explain below. |

|

|

Beside the two shown siblings of my father that were in America, there were two other brothers of his there—he was born into a family of thirteen children. None of them of course is still alive, nor is anyone in the picture. Many of their children and grandchildren are. This is some of the story concerning my arrival in the United States. 12 July 2005 |

To the top and choices | |