|

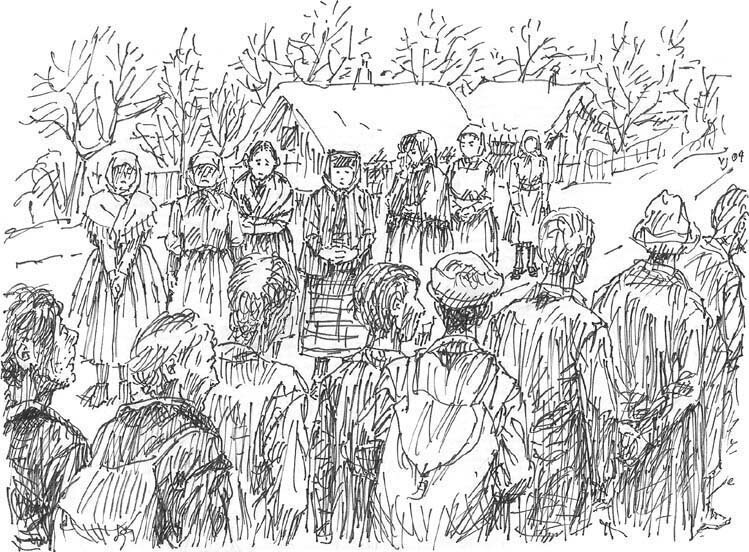

As it happens, we all left Mauthausen on that same day, at least I don't recall having remained another day. Somehow I was able to stay together with my father and brother—there was a great deal of disorganization, nobody kept a record of us as individuals. Regardless, we were marched toward a sub-camp, named Gunskirchen.

During this march I tried again, like others, to pick edible grasses on the roadside (I was the strongest then in my family), but this time we were forbidden to do so. Those of us who could did it nevertheless, when seemingly unobserved by the guards. Starvation was not a choice. The guards were few and dispersed, but on one occasion I handed some of that grass to my father and a guard spotted him eating it and kept hitting him on his back till he dropped the grass. The previously described atrocities did not happen on this march. A small incident also in my memory was that my father, who as noted used to have managerial jobs in textile factories, had in his rucksack (he still had one) some unused socks, and we tried to exchange with a guard a pair of the socks for some food. He did give us for them a piece of bread, about the size of one slice, which we had to divide among the three of us.

I don't know how long it took for us to get to Gunskirchen, it may have been a few days. This camp was the last one before liberation, by the U.S. Army. I don't know, again, how much time we spent in it, it may have been 2 or 3 weeks. At my young age then, and especially because of the state we were in, I hardly felt like counting the days, although others may have done so. There was no such thing as a calendar or any reference to time other than day and night. But these were the least of the inconveniences. The conditions were not only the worst we had undergone during the captivity, but evidently the worst recorded in history where living conditions are concerned, short of any direct acts of brutality.

It may be best to leave for next time a more detailed description of those conditions, and of finally the end of them, if not to the salvation of many of the lives.

16 February 2004

As time progressed in our marches and otherwise, we obviously became more and more emaciated because of starvation. By the time we got to Gunskirchen or during our stay there, we accordingly became the virtual skeletons widely since known and seen in many photographs and film-documentaries, as when the victims were viewed by then general Ike Eisenhower.

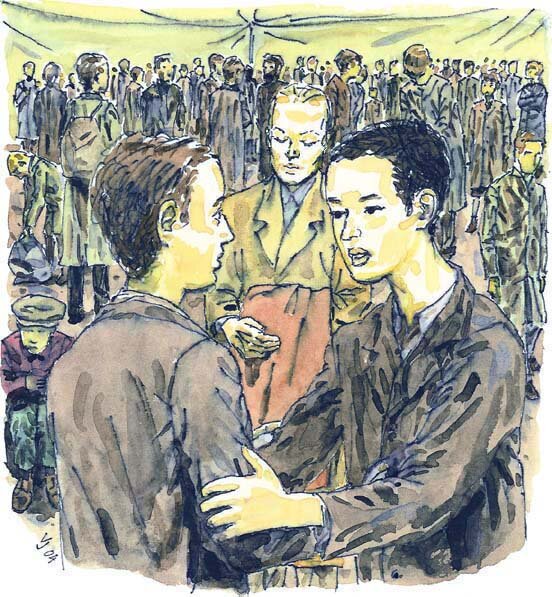

And one characteristic of that camp by the time I was in it was that it was cramped full with skeleton-like inmates, both living ones and corpses, since we were "dropping dead like flies", to use a known expression.

Speaking of cramping, I read an account by a U.S. soldier, who was part of the liberating force, that he was told that for sleep we had to lie down packed like sardines. No, we couldn't lie down at all. We were packed into "barracks"—which had no facilities and earth as the floor—so tightly that we either had to crouch all the time or stand up for relief.

As to food, we were issued to be distributed among a number of people a dried-up loaf of bread a day. All I remember is that one received a small fistful of it, and what puzzles me now is why we weren't let to die without any food at all. Perhaps they wanted us to starve to death slowly, or perhaps the International Red Cross had a minor influence. For some reason there were a few food-packages by the Red Cross that found their way into the camp. Interestingly, one of the packages, which reached a group of us of a few dozen, was at once grasped by a youthful doctor in our midst who had more strength than the others, and the food was consumed by him alone. The same doctor, by the way, was also the only person close-by who could lie down to sleep, by simply kicking his way toward more space. Although we were angry at him, he can be understood, for in these conditions anyone may be out for himself to survive.

Something similar occurred when one day we heard of an arrival of a large barrel of water near the barracks. We somehow still had some pots among us, and I took one to fetch some of the water. The barrel was on top of a wagon, on which was standing an inmate who suggested I hand him the pot and he would fill it for me. Naively I did that, and he walked away with the filled pot. I ran after him, but he was stronger and started hitting my back with some object. I found out that because I was skin-and-bones the blows were much more painful than usual.

There was performed, however, a much kinder act, too. A young fellow among us offered to bring my family some water beside his own. He did so, and the tragic irony was that the next morning we found he had died.

While languishing in the camp, we realized that our clothing was infested with lice. These turned out to carry a fatal disease, known to us as "Fleck Typhus", literally "spotted typhus", and it ultimately visited my family. In the camp, we developed the habit of destroying the lice in the manner of cracking their hard shell by squeezing them between our thumbnails.

Since anyone's death was imminent, some of us were indeed fortunate that the U.S. Army arrived shortly there. We received news at night that the Germans left the camp, fleeing the Americans. We also heard of an abandoned food storage in the camp, and since I still was relatively strongest in the family, I went there, guided by others in darkest night, to see if I can get hold of something. All I could find by then were turnips, and I stuffed as many into my knickers as I could. We ate some of them, of course, but after a while we couldn't stomach more.

A worse thing happened after daybreak. I could mention that many of the inmates had left by then, starting by themselves on their way home in their euphoria, although I don't know how many made it. The rest of us accordingly finally had enough room in the barracks, to literally stretch our legs. And alongside we speedily received some food from the Americans, perhaps too speedily. We received a lot of cans of fatty pork, though cooked, and many of us swallowed much of it immediately. As a result many suffered dysentery and soon died.

Among other events of that time I remember is that we raided nearby villages for food, and we surely must have been forgiven in our state. I recall that I picked up a chicken or part of it, probably dead, and brought it back for cooking soup for the three of us. We also somehow got hold of some of the food from the mentioned Red-Cross packages, which we included in the soup—I remember rice in particular.

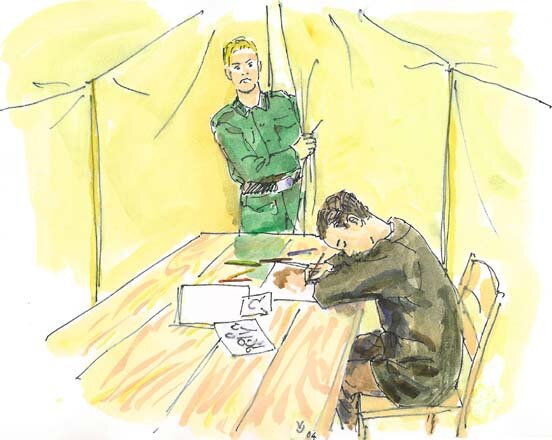

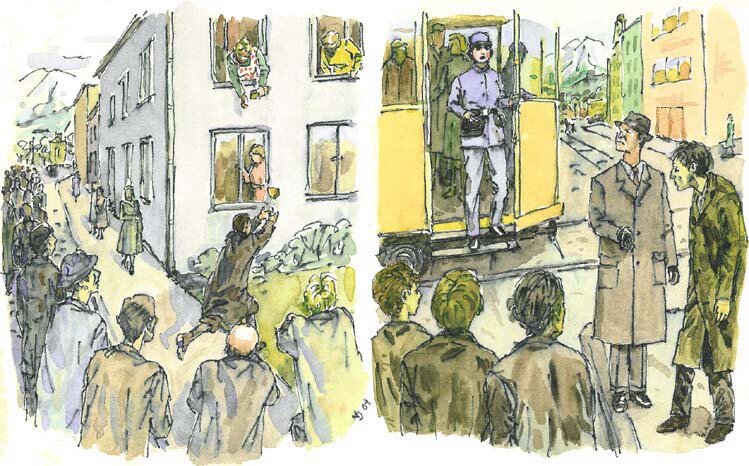

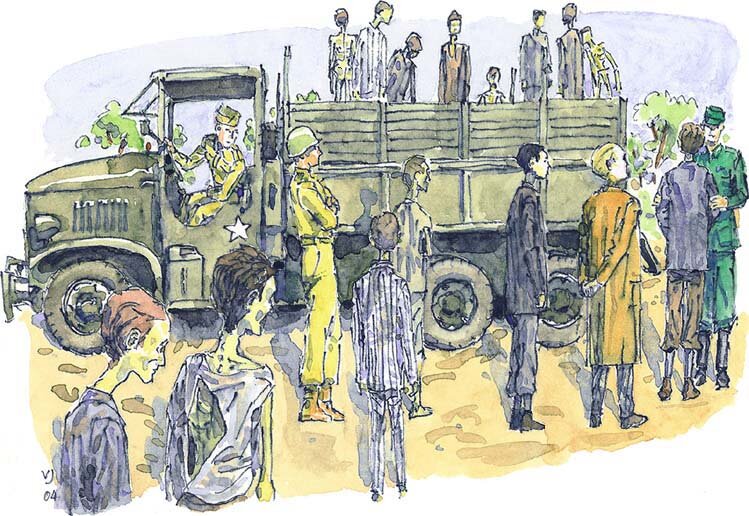

Soon the U.S. GI's, our saviors, came to take us to a provisional hospital set up in former German military quarters near the Austrian town of Hörsching. The drawing below depicts us being put on a truck. I must have been somewhat absent-minded, because suddenly I was horrified finding a German soldier taking hold of me, as shown on the far right. It turned out that as a prisoner of war he was ordered by the Americans, represented in the sketch by the helmeted officer and the driver, to lift us up into the truck. Behind me are my father and brother Hansi, and I also show other former inmates, all of us skeleton-like, if not dressed alike. Since many had shed their clothes, there may have been some without any or half-clothed in this group. Some inmates, who came to the camp from various places, had issued by the Nazis striped black&white prisoners' clothes, of which I also drew some in the picture.

|

|