|

PRESUMED IMPOSSIBILITIES, continued1, 2 PHOTOGRAPHY, continued1, 2, 3, 4 PORTRAITURE, continued1, 2, 3 COMMERCIAL ART, continued1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 AUTOBIOGRAPHY, continued1, 2, 3, 4 |

|||||||

|

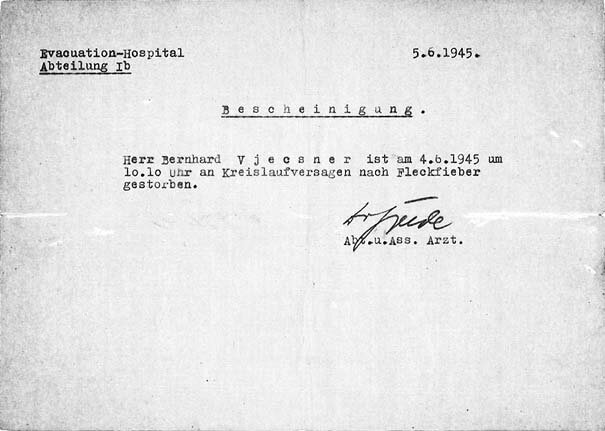

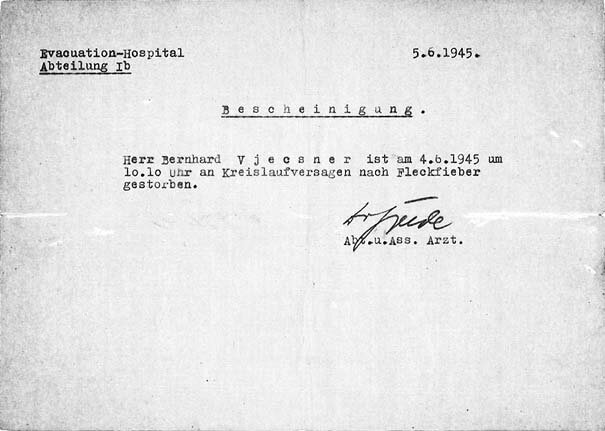

He was 45. The reason why walking was not easy for us was simply that our skeleton-like state took its toll. Remarkably, we didn't feel the full impact until we were in normal surroundings. I should first say that my brother was then weighed at about 30 kilos, a little over 66 pounds, and I at about 35 kilos, a little over 77 pounds. He was 20, and I had recently turned 19. He was about 5'9" and I am 5'9½", so my weight of about 10 pounds more meant I was slightly stronger despite the condition. The condition, of course, affected me too, regardless. Only when we were at last given beds to sleep in did I realize that because of my skin-and-bones condition I felt pain even lying on a mattress. The pressure on the bones was itself painful. (Perhaps I should note that I can only write of such observations with regard to myself, with these matters not necessarily discussed among the patients. Others understandably had their own experiences.) What I found strange in that skeletal condition was that I could feel with my hands the hollowness of the back of my hipbones, which normally are covered with the flesh of buttocks. Another experience I had was that once when I went to the bathroom I suddenly became blind. I think I yelled out that I can't see, but after a few moments my sight returned. This is the sort of effect severe starvation can have. It was accordingly astounding to me when I once saw another former victim, who had obviously already recovered to quite a degree, running outside the building. But recovery was not the fate of my brother, whose condition was gradually worsening. I don't remember him ever leaving the bed again, and my understanding was that he contracted pneumonia, an illness for which there already was a cure, but not in his so feeble condition. But although it was his lungs that were affected, presently I am not sure they weren't in some other way—or perhaps it was pneumonia after all. As can be surmised, my brother, too, died in that hospital, and after recently looking up papers I have of that period, it seems my memory needed clarification. Similarly to the above, I was given a, this time hand-written, certificate of his death. I will try again to translate it, but my German no longer being too good, and especially because of the professional language and not easy to read handwriting, there may be some lapses. Hospital II. 28th Field Hospital U.S. Army Hörsching dated 26 July 1945 Physician's Certificate Mr. Vjecsner Hans died on 25 July 1945 at 17:50 in this hospital. He was admitted on 6 May 1945 due to an abscess in the lungs. It came to a [liquefaction?] and to a [pleurisy?], which required a rib-resection. Despite continued treatment with high doses of sulfonamide, penicillin, plasma infusion and cardiazol the diseased wasted rapidly. Death set in under signs of general bodily and circulatory weakness. [Doctor's signature]

|

|

Maybe if Hansi, with his body so terribly weakened, had been administered only the antibiotic, without all the other invasive treatment, he may have lived. Not mentioned here previously was that in Gunskirchen we met a second cousin of mine, Kemény Pali (in Hungarian the last name comes first, his first name being the same as mine). He was the brother of the girl-cousin I also mentioned, the two related to us on my mother's side. Like myself, he also survived, and we were together at Hörsching before leaving there. When on a walk once on those U.S. Army grounds (the hospital was not the only place there), we stopped in front of a building occupied by a black unit (blacks and whites were separated then in the military, until president Truman put an end to it). In front was sitting one of the GI's, and I was fascinated by him because I had never seen a black in person before. I felt he had a special kind of brown beauty and asked my cousin, who spoke a bit of broken English, to inquire if I could draw a portrait of the man. I probably ended up drawing others among them as well, and what I do remember is that they took us into their kitchen and gave us meals—they knew of course that we were former victims, our makeshift clothes and still emaciated look alone giving us away. We indeed were still hungry, though obviously not left starving. As I remember, we were rationed the same kind of food each day, and there wasn't much of it. Exactly why, I am not sure. I think they didn't have much in supply—our source of food was not the same as that of the military. Accordingly I used to, like others, go to the back of the Army's mess-hall and look for leftovers the GI's threw away. At that time I no longer seemed to be with the cousin. He may have left before me, but we at some time talked about my coming to his home in Budapest. We did not know then that his whole family had survived, as did many in that city. As said elsewhere, I lived with them for a few months, before moving to Prague. Pali, the cousin, was exactly three weeks older than I, and we were both named after the same person. He died at the age of 50. There are several memories I have of my stay at Hörsching when alone. It was on that military base that I first learned of baseball. I saw GI's playing it, and it looked very strange to me, including the customary rooting noises they made. But then everything about the Americans looked strange to me, especially the atmosphere of a freedom I never knew. One day I walked into a large tent (nobody stopped me) out of which came unusual sounds. I found out that the tent served as a movie theater, and playing was a movie with Danny Kaye and Virginia Mayo. It was Wonder Man, and I didn't understand a word, but he made me laugh anyway. How I departed for my way back home I can't remember. Home is really not what was in question, since there wasn't any. I wanted to know if any member of my extended family was still alive, and afterward I would decide where to live. My drawing below may or may not have something to do with my departure. What I remember is that I hitched a ride on a jeep going to Linz, a nearby well-known Austrian city. The jeeps delighted me, as they apparently did many others. They typified to us the casual ways of the American military, compared to the stiffness of, for example, the Nazis (think of the goosestep). But whether I went to Linz just to see a city as a free person, unlike in my acquaintance with Graz, I don't know. I don't recall a ride back to the hospital, and it may be that this was the beginning of my repatriation. |

|

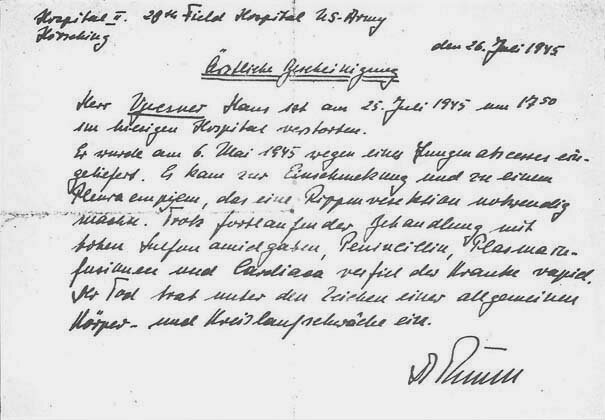

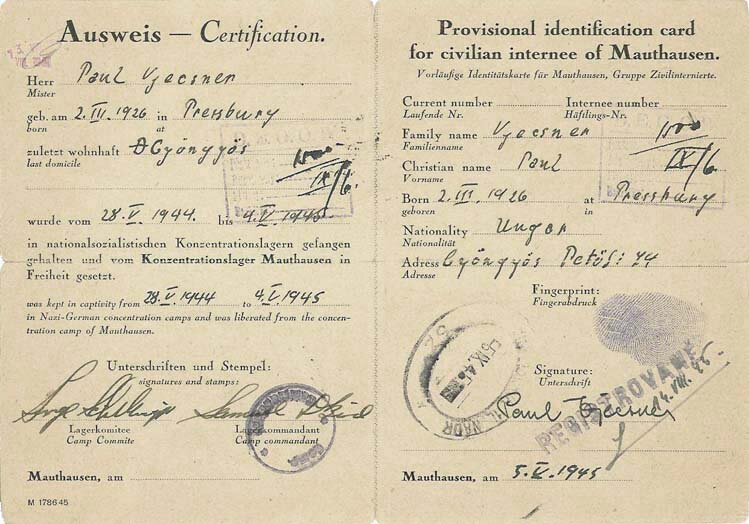

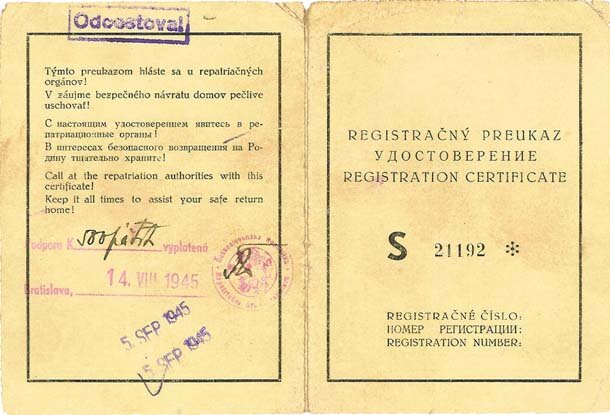

My travel back from Austria was in the company of about a dozen or more other former victims, and I doubt they came all from that base. In fact, the immediate destination of all of us was Czechoslovakia, and my former fellow-victims were mainly from Hungary. In any event, we traveled by train, and it may well be that the group was gathered together in Linz as the place of departure. I should note that we were officially helped in our repatriation, whether by the U.S. military or by governments. It may have also been an organization like the Red Cross, and I think people in charge changed throughout the trip. Whichever the case, I was able to among my papers now recover the below document issued after liberation. |

|

It is both in German and English, though the latter is very small on the left page. To explain some parts: the place of birth, Pressburg (seen on both pages), is the German name for Bratislava; the starting date of my captivity, given as 28.V.1944 (the first number, again, is the day, the second, a Roman numeral, the month), was really sometime in March of that year; "Christian name" seems a mistaken English for "First name", akin actually to the German "Vorname" used; under Nationality, "Ungar" is German for "Hungarian", although I don't think I was considered a Hungarian national then, but rather stateless; the various stamps were affixed in different places during my return and relocations. 18 March 2004 My above illustrated trip to Linz seems the start of my repatriation after all, my having researched some of the geography. On our journey to Czechoslovakia, I remember, our first stopover there was České Budějovice, a city not far from Linz. It is a city famous for its beer, as is the larger Plzeň, farther north. That they are famous will be seen from their German names, which are Budweis and Pilsen. In Budějovice we were lodged overnight for the first time, in what was probably a small hotel. I still remember what a wonderful feeling of normal life I had looking out a window and seeing below me the usual traffic of a city. My own first destination was the Slovakian town of Kremnica I spoke of before as my mother's hometown, and I wanted to find out of course if any relatives survived. I truly didn't think I would find my mother anywhere, since she was too delicate to have lived. But I did look for a while for whomever I might find, in Czechoslovakia and then Hungary. Along my way to Slovakia we stopped, with still a group of people, in Brno, the capital of Moravia, which together with Bohemia now comprises the Czech Republic. I remember we were served a meal in a restaurant, and with all of us former victims of the Nazis, some reacted with extreme awe and even servility and fear. There are other anecdotes that stick in my mind. The train carried all kinds of people, including Russian soldiers, etc. At one time a Polish passenger tried to solicit some sympathy from one of the soldiers, and having difficulty, he said that he is "polsky", a Slav like the soldier ("polsky", perhaps spelled with an "i", means "Polish"—adjectives usually are not capitalized there). The Russian responded with something like "So what, I am rusky (pronounced close to "rooskee")". My next stopover was Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia I mentioned as my birthplace. I had never seen it, though, since leaving as an infant there. When arriving there this time, the group had thinned greatly; in fact I only recall one other fellow, with whom I had a strange incident. I should note that when meeting the black American soldiers in Hörsching, Austria, they gave me and my second cousin some canned food before we left. I took some of it on my trip, and when in Bratislava, I naively asked the other fellow, lodged beside me, if he could keep an eye on the bundle, because I wanted to see a movie in town. When I came back, the fellow was gone and so was half of the bundle. On reflection, I thought he was quite decent, not having taken all of it. The movie I wanted to see, a first time for me in a movie house again, was "That Hamilton Woman", with Vivian Leigh and Laurence Olivier, he as Lord Nelson of Trafalgar fame. How I paid I am not certain, but below may be an indication. By the way, the canned food I remember was pineapple slices, which was new to me and I enjoyed greatly. The indication of payment I mentioned was apparently out of assistance I received from, I think, a Jewish organization there. Again, I can't recall all details, but the below certificate, still in my possession, explains some. |

|

||||||

|

On arriving in Kremnica, I found only two, earlier referred to, members surviving out of my extended family there, which numbered around a dozen. The survivors, again, were my cousin Maria and her gentile mother. In the following photographs I am getting a little ahead of myself, because they were taken later. I am including them in order to depict people concerned at the time I am now writing about. |

|

Here is the mother and daughter in 1951, in pictures they sent me after I had emigrated to America. I mentioned before that Maria was a beauty, and in maybe a different way so was her mother, especially when still a what may be said peasant girl. She was tremendously kind, maybe the best to me after the war. Maria, as seen, looks virtually alluring, as if conscious of her charm. They moved to Bratislava before my emigration, and by the time of these pictures she had married. |

|||

|

In this odd picture, taken in my stay in Prague, is seen, with me, a married couple from that town of Kremnica where I found my cousin and her mother. The couple was among the rare Jewish survivors in Slovakia, and what remains in my memory is that the husband (the white-haired gentleman behind me) gave me a belt when I first met them. To explain, I wore makeshift clothing then, given when in the U.S. hospital in Austria, and my trousers were held up with a string. After my war experiences this was nothing strange to me, but the man was immediately troubled by it and found a belt for me. Now as to the photo, in European cities commercial photographers often snap pictures of assumed tourists, then give them a numbered slip with which to later order copies. Then they first show rough contact prints (ones not enlargements) of the 35mm (ca.1 3/8") long pictures, of which the present one is a greatly magnified example. |

|

|

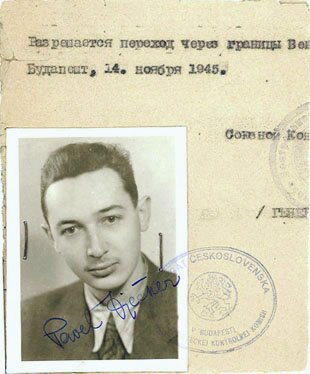

Turning attention back to the period when after the war I found my above relatives and made these acquaintances—I went on to Budapest, in keeping with discussions with the second cousin, who came from there. 20 July 2004 Whether I already knew when I went there that the cousin's whole family had survived I am not sure. Anyway, I was asked to live with them, and I did stay there for a few months, as mentioned elsewhere. At this moment I am unsure of how many months I stayed, since the above records show I arrived in Slovakia and probably Hungary in August of 1945 (I used to think it was sooner), and a below record shows I applied for a travel permit back to Czechoslovakia in November of that year. At any rate, I wasn't too happy living with the family and decided to venture on my own. The cousin's mother was my mother's first cousin and best friend, but she was somewhat stepmother-like toward me. She, for instance, affectionately fondled her returned son when he was in bed while paying no attention to me as I lay in the same room. To be sure, I didn't want to be fondled, but she made no attempt to as much as say something comforting to me. The first below picture, of this family, is again from a few years later; they sent it to me in 1949 when I was in the U.S. and in the Army. The second image does come from my period in Budapest, when I applied for the travel permit. |

|

|

|

As I wrote above, the son Pali, who was three weeks older than I, was with me late in concentration camp and afterward in the hospital. He died at 50. His father, who as appears in the photo had a sweet disposition, died earlier, and his mother more recently. The daughter, of whom I write elsewhere, is the only one still living. The second image has my ID stapled to the travel permit, seen folded. That side has Russian typing (they were the conquerors there), but the lower stamp says "DELEGATE OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA IN BUDAPEST" etc. in Slovakian. |

|

|

Evidently I still had a baby face at 19 and my clothes are ill-fitting, and that I tried to sport a mustache I don't recall. The clothes were, as I remember, my father's, which he had stored somewhere. While in Budapest, as indicated, I still made a try to find my mother, and posted her name on a board affixed to the outside of a building and listing missing victims. The search was in vain, as I understandably expected. I also made a trip to Gyöngyös, where we last lived as said before. Most Jews, of course, did not survive, but as noted where the preceding link leads to, my past woman photography employer did. I met her again on that visit, when she said she was leaving for Israel, and I will never forget the sympathetic kiss she gave me (on the cheek), which embarrassed me, coming from my former boss. Also surviving from the town was a girl cousin of mine on my father's side. She was half-a-year older than I and also lost all her family, including a sister of about 12 and a little brother about 6. She died around a decade ago. As said, after a few months in Hungary, where I did a small amount of commercial art while living with the relatives, I wanted to be independent and decided to try my fortune in Prague. 26 July 2004 |

To the top and choices | |